A talking cat may seem childish, but a tyrannical monarch calling for public executions is certainly more of an adult theme. The Alice in Wonderland books, while on the surface are for children, bring something much darker and more profound to the table that you might expect from watching the Disney animated classic.

Rumour has it that Lewis Carroll wrote these books about drugs, and while that has turned out to not actually be true, it still provides a rather interesting angle on the man. To write something so joyfully nonsensical and so mind-twistingly interesting that you’d tie yourself in knots trying to unwrap all the layers of this literary pass the parcel of innuendo and double meaning, you’d think that he’d have to at least dabbled in the many legal drugs of the time. However, the true story behind the books is that he was on a boat with a young girl called Alice and told her about his idea and she told him he should write it.

With such a plain origin, perhaps it’s understandable why so many people choose to believe he just wrote the books on a drug-fuelled adventure into nonsense. However, Carroll was known to go sailing with children and families, and was all around known as a caring man who allegedly once took a stray cat to the vet to get a fish hook removed. While rumours of his relations with the children have, since the 1930s, been restless, there is actually almost no evidence that anything unseemly ever happened, and it is generally believed now that those rumours arose more as a result of the inclination of some writers towards Freudian ideas at the time.

Amongst the most political elements of either of the Alice books, The Walrus And The Carpenter can easily be read as anti-capitalist, or anti-imperialist, or anti-industrialist, or why not a combination of all three? To summarise the latter half of the poem, the walrus, a potential representation of capitalism, exploits some oysters for their about and then proceeds to eat them. The Alice books are famously quite nonsensical and open to interpretation, but it seems hard to interpret that poem in a way that doesn’t cast the oysters as an oppressed group like the proletariat or developing countries, or perhaps the environment. “It seems a shame … to play them such a trick” being said before the walrus proceeds to eat the oysters certainly plays into the anti-capitalist interpretation, emphasising the exploitative relation between the walrus and the oysters.

The glaringly obvious cartoonish portrayal of the monarchy makes the idea that the books themselves are a critique of the monarchy quite simple to pick out. Notably, Alice herself seems to feel very little respect towards the queen’s status as a royal, perhaps alluding to a wider message against the idea of having a monarchy so detached from everyday people. In fact, in the first meeting between Alice and the King and Queen of Hearts, while the other characters immediately laid face-down on the ground in a show of respect, Alice is instead said to be ‘doubtful and “stood where she was, and waited”, showing no physical sign of respect towards the monarchy even when it was clearly conventional to do so. Then, there is, of course, the words of the queen herself, “Off with his head!”. Whether or not Carroll meant anything bad towards Queen Victoria, the Queen of Hearts is certainly shown as petty and controlling right from the start, executing people for being better than her at croquet.

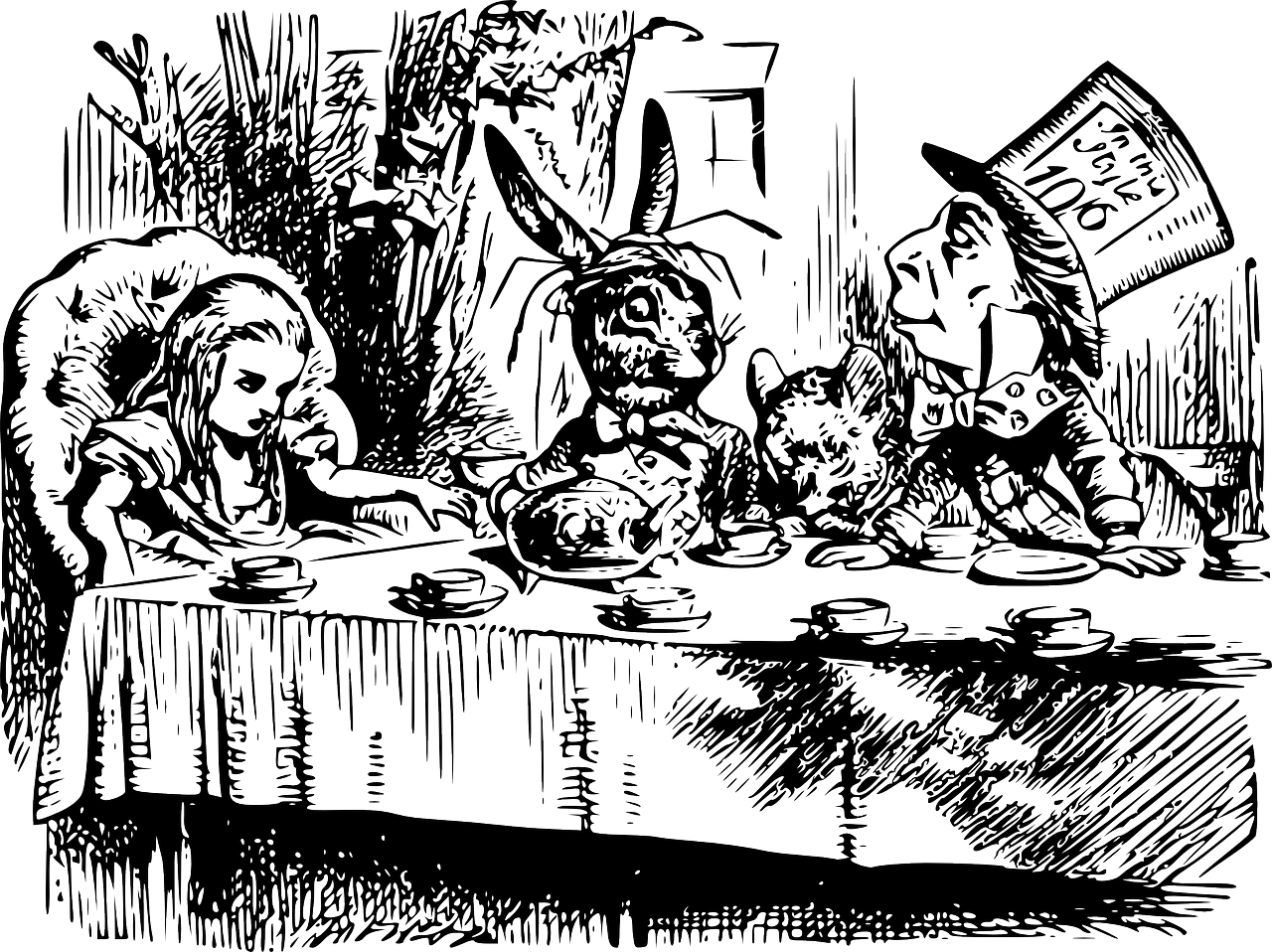

It is also important to pay close attention to the illustrations in the Alice books just as much as the words, as they too have their secrets. For example, The Mad Hatter is Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. Whether this is due to a request from Carroll or just illustrator John Tenniel having some fun is unclear, but there is something to be said about the fact the character who looks exactly like the Prime Minister is a mad hatter at an eternal tea party, sentenced to death for “murdering the time”.

Nothing can really be said with absolute certainty about these books, and perhaps there’s something a bit unnecessary about scouring children’s books for political messaging, but there is certainly room to interpret these books in a political light.

[…] Will. 2021. ‘“We’re All Mad Here”: The Politics of Alice in Wonderland’, The Witness 21 Jan. […]