Despite legal and awareness efforts, one of the world’s most painful and harmful traditions continues to impact millions of women each year. Female genital mutilation, or FGM for short, involves the removal or cutting of the female genitalia and occurs largely across a belt of African countries, as well as areas in the Middle East and Asia. The World Health Organisation defines FGM as a “procedure that injures female genital organs for non-medical reasons” and a practice that can lead to severe long-term physical and mental health problems.

As of 1985, the practice has been outlawed in the UK under the Prohibition of Female circumcision Act. However, the legislation has also been strengthened and updated through the female genital Mutilation Act 2003, with further amendments in 2015, to provide greater protection and safeguarding for those at potential risk of FGM. Under the provisions of the legislation, there is now a legal requirement enforced on healthcare professionals and teachers to report any cases of FGM in under-18s to the police.

However, despite these measures-including the forbiddance to take girls overseas for FGM during the so-called cutting season, FGM continues to affect an estimated 137,000 girls in England and Wales today.

To understand why FGM persists, it is important to consider the structural factors that allow its continuation. A key element of this is culture. Those who have practised FGM justify its harmful nature by calling it a tradition, passed down from one generation to the next. In this way, the practice is often seen as a means of preserving the cultural identity of the girl through the reinforcement of values.

In other countries, cultural factors are also linked to their persistence, particularly through fixed gender roles and perceptions of women and girls as gatekeepers of their family honour. These roles are tied to strict ideas regarding women’s sexual purity and control over women’s lack of desire. There is an idea that girls’ sexual desire must be controlled through FGM to prevent sexual activity and immorality.

However, other cultures justify it on hygiene and aesthetic grounds. Over the years, communities have come to see female genitalia as filthy and framed a girl who is not cut as unclean. Where such beliefs are evident, a girl’s chance of getting married is severely decreased, as it is considered to make her unattractive. Type III FGM, Infibulation, for instance, is thought to achieve smoothness which is viewed as aesthetically pleasing. In turn, these beliefs cause a strong social and cultural pressure for girls and families to conform to the practice that has been evident within communities for years.

However, while it is evident that culture plays a significant role in the persistence of FGM, other factors, such as religion, also contribute to its prolonged existence. Female genital mutilation is commonly practised in countries across the belt of Africa and areas of the Middle East and Asia. Although the practice is linked to religion, it is not tied to any particular faith and predates both Christianity and Islam. In Islam, for instance, Sharia Law puts the rights of the child first, and the Muslim Women’s League upholds the practice as a strict violation of the Quran. Nevertheless, in some religious communities, FGM is commonly believed to be a mandatory requirement to be a follower. This has been supported and implemented by religious leaders such as priests or imams who have retained beliefs of there being individual spirits or supernatural forces, which make the continuation of the practice vital. Clearly, the strength of these religious misinterpretations highlights how the harm of FGM is allowed to exist and continue through communities.

In conclusion, FGM persists due to the deep-rooted cultural traditions, social pressures and religious misconceptions. Despite laws and awareness efforts, these factors continued to drive the practice, showing that lasting change requires not just legislation but community-led education and empowerment.

Edited by Elizabeth Pinkney

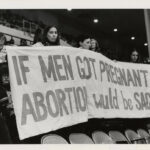

Image: James Fulker, 2013 CC BY-SA 2.0

Average Rating